Instruction

Is Lag Slowing Your Swing Down?

In my last article, “Who is the Greatest Driver of the Ball, Ever?” we introduced the techniques that separate the longest drivers of the golf ball from most amateur and tour players. We established that the turning and thrusting system of the legs, pelvis and torso is the motor and primary energy generator in the golf swing. The supple arms wind tightly up and around this system on the backswing, and then simply react to it and unwind on the through swing creating a slinging effect. The energy from the turning and thrusting system is transferred through the arms and club shaft, creating tremendous escape force out to the club head. Being that the wrists are the key joints that connect the arms to the club, they understandably play a key role in the golf swing.

In my last article, “Who is the Greatest Driver of the Ball, Ever?” we introduced the techniques that separate the longest drivers of the golf ball from most amateur and tour players. We established that the turning and thrusting system of the legs, pelvis and torso is the motor and primary energy generator in the golf swing. The supple arms wind tightly up and around this system on the backswing, and then simply react to it and unwind on the through swing creating a slinging effect. The energy from the turning and thrusting system is transferred through the arms and club shaft, creating tremendous escape force out to the club head. Being that the wrists are the key joints that connect the arms to the club, they understandably play a key role in the golf swing.

All too often I see players at the range, and even as part of a pre-shot routine, setting an angle with the wrists between the forearms and club shaft and preserving that angle in a pumping action as they rehearse their swing. Very often I’ll inquire with these players what they are doing and why, and it is always the same response:

“I want to hold the angle and delay my release for as long as possible, to create lag…you know, avoid the cast.”

This becomes the perfect place to begin our examination of the role of the wrists in the golf swing.

So let’s talk a little more about “lag” and “release,” as these are hot topics and much disputed in the world of golf instruction. How to generate lag and its importance is frequently debated in golf circles as it is widely accepted to be a key facilitator of club head speed. Modern swing viewpoints are that lag is created by “holding the angle” between the club shaft and forearms for as long as possible, or “delaying the release” of the wrists into impact.

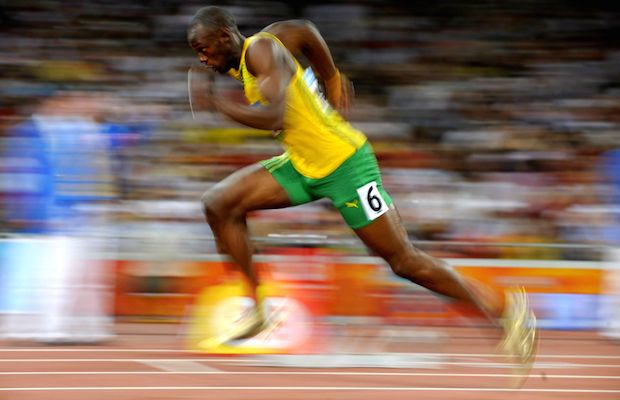

The term “lag” is defined as “a failure to respond in a timely fashion to inputs.” “Holding” and “delaying” are terms describing restrictive forces requiring some type of tension, and indicate an interruption in movement. We would never ask someone cracking a whip or casting a fishing rod to “hold” or “delay” anything, in fact, we would encourage them to do just the opposite. Just as it would be absurd to suggest to the greatest sprinter in the world, Usain Bolt, to hold off on his top speed for the first half of the race, but then really turn it on towards the end of the race.

We only have so much time and circular path distance in the golf swing to maximize the speed of the club head, and we need to take full advantage of these time and distance parameters.

I prefer to describe “developing lag” as simply the full “loading” of the wrists, forearms and elbows. Maximum loading is the result of tension free wrists, forearms and elbows hinging and rotating their complete, natural range of motion. The more tension we have, the less likely these joints will move through their complete range of motion, and as a result loading will be decreased.

The facts are that in the downswing, the earlier and faster we begin “unloading” the wrists, forearms and elbows, the more time and distance there is to turbo charge the slinging arms that are reacting to the bigger circular forces being generated by the turning and thrusting system. Therefore, the trick is to completely load the wrists, forearms and elbows on the back swing — we don’t have to wait for the lag to be created on the downswing — so that we can unload and compliment the slinging action of the arms from the very top. This gives us more time and circular distance to advance the shaft and increase club head speed.

The importance of the turning and thrusting system serving as the primary energy generator (with the wrists, forearms and elbows serving as the turbocharger) can not be overstated. This is evidenced by comparing the top long drivers with the top PGA players. According to Dr. Greg Rose from the Titleist Performance Institute, PGA players have a rotational force of about 900 degrees per second and world class long drivers are at about 1300 degrees per second. At the same time, long drivers have considerably more thrust, which creates the hip vault that results in de-weighting them at impact as compared to most tour players, who are considerably “heavier” at impact. Combine these rotational and thrust force advantages with a more complete loading and an earlier unloading of the wrists, forearms and elbows results in the dramatic distance differences between the two groups.

A good visual to help understand how to release the fully loaded wrists, forearms and elbows earlier and faster is the chore of beating the dust out of a carpet hanging from a clothes line. For our purposes, we are going to use a golf club. Would you finish the chore faster by holding the angle of the wrists as the arms pull across the body, making contact with the carpet with the butt of the club and hand unit or left elbow? Or, would you be more effective using your turning and thrusting system to sling the arms into the carpet at tremendous speed, while the wrists, forearms and elbows unload considerably earlier serving to further advance the shaft so that the club head slams into the carpet? Just as the second scenario will get you finished with your chore faster, it will also help you increase your club head speed and distance.

Release is when the lag or load created begins to reverse itself, or “releases” into the mirror image. It is the moment these wrist, forearm and elbow positions reverse themselves that is considered the full “release” of the club.

Players who try to hold angles or practice “pump” drills to improve their release are fighting a losing battle. Every repetition they practice this technique is actually reducing the time and circular distance they have to build up speed. They are actually slowing their club head speed down by delaying the release. Instructors use this same “pump” drill on beginners to get them to eliminate “casting” the club. Casting the club being a bad thing is another age old instructional misnomer. Why do we cast a fishing rod? To get the lure (or in golf’s case, the club head) moving as fast as possible so it can fly further. The casting actions of the elbows and shoulders are very similar to the proper arm movements in the golf swing; they just occur in a different plane.

Note: Notice that I didn’t include the wrists, because casting uses a wrist pivot which needs to be avoided. More on this in a subsequent article.

Jack Nicklaus said, “There is no such thing as a cast, just a slow lower half.” So, as golfers wrongly try to eliminate the “cast,” what they should really be doing is focusing on activating and accelerating their turning and thrusting system.

In short, our turning and thrusting system is slinging the unwinding arms out to the ball, as the straightening of the right elbow, supination of the right forearm and unhinging of the wrists are turbocharging the club head and advancing it further along the circular path. We are slinging the arms and throwing the club head with the wrists at the same time — a key to the tremendous distance generated through the Wind and Sling golf swing.

In Memoriam

Last month I posted “Who is the Greatest Driver of the Ball, Ever?” In it, I highlighted the accomplishments of the Legend of Long Drive, Mike Dunaway. Thank you for your overwhelming response. Sadly, my friend and mentor passed away on September 29th, 2014 at the age of 59. Please click here and check out the video tribute of his life and his love for golf.

Hit’em long and straight forever, Mike. Thank you for all you’ve done for me. Swing in peace.

Instruction

The Wedge Guy: Beating the yips into submission

There may be no more painful affliction in golf than the “yips” – those uncontrollable and maddening little nervous twitches that prevent you from making a decent stroke on short putts. If you’ve never had them, consider yourself very fortunate (or possibly just very young). But I can assure you that when your most treacherous and feared golf shot is not the 195 yard approach over water with a quartering headwind…not the extra tight fairway with water left and sand right…not the soft bunker shot to a downhill pin with water on the other side…No, when your most feared shot is the remaining 2- 4-foot putt after hitting a great approach, recovery or lag putt, it makes the game almost painful.

And I’ve been fighting the yips (again) for a while now. It’s a recurring nightmare that has haunted me most of my adult life. I even had the yips when I was in my 20s, but I’ve beat them into submission off and on most of my adult life. But just recently, that nasty virus came to life once again. My lag putting has been very good, but when I get over one of those “you should make this” length putts, the entire nervous system seems to go haywire. I make great practice strokes, and then the most pitiful short-stroke or jab at the ball you can imagine. Sheesh.

But I’m a traditionalist, and do not look toward the long putter, belly putter, cross-hand, claw or other variation as the solution. My approach is to beat those damn yips into submission some other way. Here’s what I’m doing that is working pretty well, and I offer it to all of you who might have a similar affliction on the greens.

When you are over a short putt, forget the practice strokes…you want your natural eye-hand coordination to be unhindered by mechanics. Address your putt and take a good look at the hole, and back to the putter to ensure good alignment. Lighten your right hand grip on the putter and make sure that only the fingertips are in contact with the grip, to prevent you from getting to tight.

Then, take a long, long look at the hole to fill your entire mind and senses with the target. When you bring your head/eyes back to the ball, try to make a smooth, immediate move right into your backstroke — not even a second pause — and then let your hands and putter track right back together right back to where you were looking — the HOLE! Seeing the putter make contact with the ball, preferably even the forward edge of the ball – the side near the hole.

For me, this is working, but I am asking all of you to chime in with your own “home remedies” for the most aggravating and senseless of all golf maladies. It never hurts to have more to fall back on!

Instruction

Looking for a good golf instructor? Use this checklist

Over the last couple of decades, golf has become much more science-based. We measure swing speed, smash factor, angle of attack, strokes gained, and many other metrics that can really help golfers improve. But I often wonder if the advancement of golf’s “hard” sciences comes at the expense of the “soft” sciences.

Take, for example, golf instruction. Good golf instruction requires understanding swing mechanics and ball flight. But let’s take that as a given for PGA instructors. The other factors that make an instructor effective can be evaluated by social science, rather than launch monitors.

If you are a recreational golfer looking for a golf instructor, here are my top three points to consider.

1. Cultural mindset

What is “cultural mindset? To social scientists, it means whether a culture of genius or a culture of learning exists. In a golf instruction context, that may mean whether the teacher communicates a message that golf ability is something innate (you either have it or you don’t), or whether golf ability is something that can be learned. You want the latter!

It may sound obvious to suggest that you find a golf instructor who thinks you can improve, but my research suggests that it isn’t a given. In a large sample study of golf instructors, I found that when it came to recreational golfers, there was a wide range of belief systems. Some instructors strongly believed recreational golfers could improve through lessons. while others strongly believed they could not. And those beliefs manifested in the instructor’s feedback given to a student and the culture created for players.

2. Coping and self-modeling can beat role-modeling

Swing analysis technology is often preloaded with swings of PGA and LPGA Tour players. The swings of elite players are intended to be used for comparative purposes with golfers taking lessons. What social science tells us is that for novice and non-expert golfers, comparing swings to tour professionals can have the opposite effect of that intended. If you fit into the novice or non-expert category of golfer, you will learn more and be more motivated to change if you see yourself making a ‘better’ swing (self-modeling) or seeing your swing compared to a similar other (a coping model). Stay away from instructors who want to compare your swing with that of a tour player.

3. Learning theory basics

It is not a sexy selling point, but learning is a process, and that process is incremental – particularly for recreational adult players. Social science helps us understand this element of golf instruction. A good instructor will take learning slowly. He or she will give you just about enough information that challenges you, but is still manageable. The artful instructor will take time to decide what that one or two learning points are before jumping in to make full-scale swing changes. If the instructor moves too fast, you will probably leave the lesson with an arm’s length of swing thoughts and not really know which to focus on.

As an instructor, I develop a priority list of changes I want to make in a player’s technique. We then patiently and gradually work through that list. Beware of instructors who give you more than you can chew.

So if you are in the market for golf instruction, I encourage you to look beyond the X’s and O’s to find the right match!

Instruction

What Lottie Woad’s stunning debut win teaches every golfer

Most pros take months, even years, to win their first tournament. Lottie Woad needed exactly four days.

The 21-year-old from Surrey shot 21-under 267 at Dundonald Links to win the ISPS Handa Women’s Scottish Open by three shots — in her very first event as a professional. She’s only the third player in LPGA history to accomplish this feat, joining Rose Zhang (2023) and Beverly Hanson (1951).

But here’s what caught my attention as a coach: Woad didn’t win through miraculous putting or bombing 300-yard drives. She won through relentless precision and unshakeable composure. After watching her performance unfold, I’m convinced every golfer — from weekend warriors to scratch players — can steal pages from her playbook.

Precision Beats Power (And It’s Not Even Close)

Forget the driving contests. Woad proved that finding greens matters more than finding distance.

What Woad did:

• Hit it straight, hit it solid, give yourself chances

• Aimed for the fat parts of greens instead of chasing pins

• Let her putting do the talking after hitting safe targets

• As she said, “Everyone was chasing me today, and managed to maintain the lead and played really nicely down the stretch and hit a lot of good shots”

Why most golfers mess this up:

• They see a pin tucked behind a bunker and grab one more club to “go right at it”

• Distance becomes more important than accuracy

• They try to be heroic instead of smart

ACTION ITEM: For your next 10 rounds, aim for the center of every green regardless of pin position. Track your greens in regulation and watch your scores drop before your swing changes.

The Putter That Stayed Cool Under Fire

Woad started the final round two shots clear and immediately applied pressure with birdies at the 2nd and 3rd holes. When South Korea’s Hyo Joo Kim mounted a charge and reached 20-under with a birdie at the 14th, Woad didn’t panic.

How she responded to pressure:

• Fired back with consecutive birdies at the 13th and 14th

• Watched Kim stumble with back-to-back bogeys

• Capped it with her fifth birdie of the day at the par-5 18th

• Stayed patient when others pressed, pressed when others cracked

What amateurs do wrong:

• Get conservative when they should be aggressive

• Try to force magic when steady play would win

• Panic when someone else makes a move

ACTION ITEM: Practice your 3-6 foot putts for 15 minutes after every range session. Woad’s putting wasn’t spectacular—it was reliable. Make the putts you should make.

Course Management 101: Play Your Game, Not the Course’s Game

Woad admitted she couldn’t see many scoreboards during the final round, but it didn’t matter. She stuck to her game plan regardless of what others were doing.

Her mental approach:

• Focused on her process, not the competition

• Drew on past pressure situations (Augusta National Women’s Amateur win)

• As she said, “That was the biggest tournament I played in at the time and was kind of my big win. So definitely felt the pressure of it more there, and I felt like all those experiences helped me with this”

Her physical execution:

• 270-yard drives (nothing flashy)

• Methodical iron play

• Steady putting

• Everything effective, nothing spectacular

ACTION ITEM: Create a yardage book for your home course. Know your distances to every pin, every hazard, every landing area. Stick to your plan no matter what your playing partners are doing.

Mental Toughness Isn’t Born, It’s Built

The most impressive part of Woad’s win? She genuinely didn’t expect it: “I definitely wasn’t expecting to win my first event as a pro, but I knew I was playing well, and I was hoping to contend.”

Her winning mindset:

• Didn’t put winning pressure on herself

• Focused on playing well and contending

• Made winning a byproduct of a good process

• Built confidence through recent experiences:

- Won the Women’s Irish Open as an amateur

- Missed a playoff by one shot at the Evian Championship

- Each experience prepared her for the next

What this means for you:

• Stop trying to shoot career rounds every time you tee up

• Focus on executing your pre-shot routine

• Commit to every shot

• Stay present in the moment

ACTION ITEM: Before each round, set process goals instead of score goals. Example: “I will take three practice swings before every shot” or “I will pick a specific target for every shot.” Let your score be the result, not the focus.

The Real Lesson

Woad collected $300,000 for her first professional victory, but the real prize was proving that fundamentals still work at golf’s highest level. She didn’t reinvent the game — she simply executed the basics better than everyone else that week.

The fundamentals that won:

• Hit more fairways

• Find more greens

• Make the putts you should make

• Stay patient under pressure

That’s something every golfer can do, regardless of handicap. Lottie Woad just showed us it’s still the winning formula.

FINAL ACTION ITEM: Pick one of the four action items above and commit to it for the next month. Master one fundamental before moving to the next. That’s how champions are built.

PGA Professional Brendon Elliott is an award-winning coach and golf writer. You can check out his writing work and learn more about him by visiting BEAGOLFER.golf and OneMoreRollGolf.com. Also, check out “The Starter” on RG.org each Monday.

Editor’s note: Brendon shares his nearly 30 years of experience in the game with GolfWRX readers through his ongoing tip series. He looks forward to providing valuable insights and advice to help golfers improve their game. Stay tuned for more Tips!

Alan Harris

Jan 23, 2022 at 3:00 pm

Your approach to the question leads to ambiguity.

Issues in the analysis and subsequent discussions seem to hinge on word definitions and the intended context. The only certainty is in the physics, primarily the physics related to angular momentum and it’s conservation.

“For the same body, angular momentum may take a different value for every possible axis about which rotation may take place.[12] It reaches a MINIMUM when the axis passes through the center of mass.”

The hands are involved as a lever (force multiplier) and a determiner of the radius and axis of rotation. Up until impact is the opportunity to build angular momentum. And at that point ,to have ideal contact the determiners (radius and axis is fixed). Angular momentum is maximized when the ratio between the distance the hands travel and the distance the clubhead travels is maximized.

The trick then is to know how to properly manage the axis in order to have built to maximum angular momentum by the point at which it is needed. (and we know that no angular momentum is being built at the point where the axis of rotation passes through the center of mass.

The swing is a physical system. Model it, apply the physics and you’ll have an unambiguous answer.

Toño

Oct 22, 2014 at 1:53 am

I think that they are getting crazy out there with the definitions. The LAG is caused by the inertial forces, the extension of the dual lever( palo wrist Wrist arm) by the centrifugal force ,the acceleration of palo is parametric and this is produced by the movement of the shaft and this moves thanks to the ground ( 3 law of Newton ). Now if you want to develop explanations of each of the parties.

Ewan S Fallon

Oct 21, 2014 at 2:27 pm

Sorry but Mike Dunaway learned from Mike Austin and never did match him. Austin and Colsaert were and are the longest drivers with the least effort. Neither use rotation to get velocity, instead used a crack of the whip to accelerate the clubhead. The hands are slowed and cause this acceleration. A rotating system cannot slow the hands as the hips rotate without causing a flip or a wild slice.

Anon

Oct 20, 2014 at 11:03 pm

To eliminate casting, don’t go as hard from the top of the swing. Smoothly accelerate from the top and your wrists will unhinge naturally at the bottom of your arc. Casting comes from trying to accelerate from the top of the backswing too quickly.

Brandon

Oct 20, 2014 at 6:21 pm

truth be told, golf is the only stick/ball sport on the planet where lag is seen as a power producer. The pic of Mr. Duke above at impact with the rug is almost the same exact impact image that you would see a MLB slugger in at perfect impact. They are not holding the head back at all when their hands reach the ribcage on the way down.

If you hold the lag, you eliminate the part of your free swinging leverage in the pendulum that is accelerated by gravity. It costs a golfer his “Freddie Couples” easy distance. If lag was really that much of a power producer, then why aren’t Lucas Glover and Sergio the longest on tour. JMHO though.

Mark

Oct 21, 2014 at 12:31 pm

You need to reevaluate your thoughts on baseball. Lag is THE power producer in baseball. Extension is a myth, it occurs after the ball has left the bat (don’t believe me? Google any picture of a homerun hitter when ball is in contact with their barrel). The top hand is bent, sometimes even at 90*, at contact.

In addition, I have an issue with the biomechanics of this article. Lag will never slow down your swing. Ever. Not releasing it can cause issues, but look at the wording…. Release.

You don’t physically force your club head onto the ball with hands and arms. This is a push move and is biomechanics lily in effecient. Lag works because it creates the opportunity for torque multiplication. As you coil, the hands continue to work back for a split second longer than your body. This results in multiple locations of torque in your swing. The body transitions from loading to unloading and your hands are either a) working back and on plane, or b) delaying their forward move. Either way you get that torque (felt as a stretch or tension) and as you ultimately progess to the ball you release the torque into the target with your hands and arms supplying control but not power.

Don’t believe me? Thrown a jab then throw a hook. Which one has more force? Jab is a push with your arm and relies on your arms ability to accelerate the hand. The hook gets body involved and your arm is working back as your body turns forward. TORQUE!!!!!!

In fact, if your hands push early, you break the kinetic chain you just created with your body and the club ends up with less impact force.

Still don’t believe me? Force = mass x acceleration. Acceleration is the change in velocity over time. The more lag you maintain, the more your club head accelerates into impact (it changes speeds more rapidly in a shorter time), and the more force you apply into the ball.

Still don’t believe me? Go hit balls with your arms and enjoy less distance and more slice. (Slice because the hands getting early extension causes path issues).

Every single stick sport relies on lag. For that matter, so does every sport period. Lag simply is the body’s way of creating torque and it is the most biomechanicly effecient move for organic power production.

I’m blow away every time I meet people who don’t get this. Let your body do the naturally designed movement. Effeciency is beauty.

Tom Duke

Oct 21, 2014 at 3:11 pm

Thanks for your reply and interest Mark–interesting perspectives.

In every stick sport, the arms, in accordance with angular momentum must move away from the turning force towards full extension. They have to, unless that natural path is redirected with tension. In fact, the tighter the arms and club are winded around the turning system, the less slack there will be in the system and the faster they will ultimately exit away once they react to the turning force. This is why every MLBB power hitter’s left arm is fully extended at impact, as is every golfers.

The right arm is also on its way to extension, as it is unloading as described in the article. Most often, still photography captures impact where the right elbow has not quite made it to full extension, but it is working that way–this is why the biggest bombs in baseball and golf are hit when the right elbow has gone from flexion to almost full extension (at which point the left elbow begins to fold, as both arms should never be straight in any stick and ball swing at the same time). This is why “throwing the head” is a big time coaching point at the major league and other advanced levels in the game of baseball–the same action detailed in the beat the carpet drill. “Throwing” anything requires the right elbow and wrist to go from flexion to extension (pushing), while the forearm rotates. So the arms are slinging around to the ball while at the same time we are further advancing the shaft and head through the unloading of the right arm–there is nothing being held or delayed. Please don’t take too big of an issue with these biomechanics, as guys like Cruz, Stanton and Trout, along with the likes of Joe Miller and the longest drivers in the world would be out of business–and I love watching them sling and throw the head!

Mark

Oct 21, 2014 at 3:56 pm

I played in the major leagues 2010/2011 and minors for 7 seasons. I’ve watched literally every player you mentioned… Not one of them has extension at contact. None. Not on a good swing at least. They do sling the bat… I guess I just don’t agree with the lag definition. In baseball, or golf, lag is the barrel or club head maintaining it’s angle in relation to the body as you approach contact.

In golf, the ball doesn’t move, so the extension can occur earlier to gain a straighter path, but in baseball, there is actually more lag than golf. It allows for adjustability.

The extension is a product of the hand following thru at impact. It’s not at all what causes or imparts power/force.

By definition, elite athletes are biomechanically effecient, that is what makes then elite.

Efficiency allows for the most force with the least effort. No one that throws hard pushes the baseball. Nobody that hits for power pushes the barrel. Like you said yourself, they whip it.

To whip it you have to first lag it and then release. The release will result in extension.

Mark

Oct 21, 2014 at 4:10 pm

To clarify. I am talking about top hand (right arm for a right handed hitter) not being extended. The left arm is extended, but only as a product of being across the body and in the opposite side of the chest from the ball. But neither arm is extended towards the incoming ball. To do so would force the player to hit the ball further out front and decreases the ability to let the ball travel. This increases relative velocity of incoming pitch. That’s not a good thing. It’s actually talked about a bunch of how good hitters stay “tight to body” with the lead arm, whereas poor hitters force bat out front. In addition, the left arm for a right handed hitter does very little in good hitters. It’s fairly straight through the whole swing, and if it extends, it does so in the opposite direction relative to the pitch. There is a reason why Latin hitters dominate the game today. The American kids are instructed poorly to push the barrel and the Latin kids, getting less instruction, actually develop more naturally effecient swings. Efficiency is natural, but if you practice bad swings enough, then you program bad habits and lose your natural effecientcy.

Go look at the best hitters, their top arm is bent at contact, and that is ideal. In golf, the ball is further away from you and below you, so you do reach some as you release, but you still cannot force barrel forward and whip it. They are opposite processes and whipping it from a lagged position creates more acceleration an force.

Tom Duke

Oct 22, 2014 at 12:11 am

The various interpretations of certain words can make written discussions like this difficult.

Extension in the elbow is considered “the bringing of limbs into a straight position, or to full length”–(nothing to do with positioning them with the shoulder). Note I specified in my last reply “left arm fully extended…right elbow has not quite made it to full extension, but it is working that way”.

In every one of the photos that follow of the Long Drive World Champs and the baseball players referenced, you will see the left arm is fully extended and the right arm very much on its way there…if not all the way there in Miller and Winther. And while I did not achieve your level of success in pro ball (I was a 4th rounder long ago), all of these swings would be considered very good to great by the players performing them.

In any throwing motion, a key part of the motion is the elbow going from flexion into extension (as well as the scapula going from adduction to abduction). Being that the elbow is a simple hinge joint, it can only function in a straight line. (The rotational characteristics of the forearm and shoulder allow it to be perceived as it is working in something other than a straight line.) Accelerating this straight-lined extension of the right elbow with the tricep plays a key role in our unloading, and does in fact lead to bat/shaft advance that further accelerates the primary slinging action created by the turning and thrusting system of the legs, pelvis and torso that runs out the drive shaft of the “connected” left arm to the club head. The arms react to the turning and thrusting system (not outrace it), which allows our left arm to be extended, but still partially winded across the torso so we can come into impact more off the right hip as demonstrated in the carpet beating photo from the article, and in all the photos below. It is also why world class long drivers reduce the angle of the right elbow at the top considerably more than most tour players as they recognize the importance of elbow extension as part of our “unloading” to increase head speed. I encourage you to take a club and go beat a carpet…first with both arms straight…then with a little hinge in your right elbow, and then with as much hinge as you can put into the right elbow and see which “style” of beating delivers the fastest strike. So I guess we are going to have to disagree that the extension “is not at all what causes or imparts power/force”.

Some great shots here, sorry I couldn’t link them…good luck!

http://www.mygolfway.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/REMAX-WLDC2012.jpg

Ryan Winther, World Champ

http://www.hititlonger.com/images/uploads/blog/JoeMillerRelease2.jpg

Joe Miller, World Champ

http://thesportscrave.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/stanton.jpg

Carlos Stanton

http://usatthebiglead.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/mike-trout1.jpg?w=441

Steve Trout

http://190.9.128.163/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/miguel_cabrera_2.jpg

Miguel Cabrera

jim jones

Oct 21, 2014 at 6:47 pm

You have to retard the pivot or shoulder rotation in order to release from a conscious delay of the uncocking of the wrists. This will also not allow you to get your body mass through the ball. Also Centrifugal acceleration increases exponentially so the sooner the acceleration begins the better. Also there are different releases of the wrists. From the top you ulnar deviate the left wrist to get the club moving but you still maintain the dorsiflexed right wrist so that snap of the wrists happens at the bottom with the clubhead already travelling very fast, so in esscence you’re rapidly accelerating an already fast moving object and increasing the hypothetical mass of the club with the mass of your body coming through as well.

CD

Oct 20, 2014 at 5:05 pm

I think you mean probation of the right forearm not supination?

Excellent article though. People in my op. mistake cause and apparent, visual effect.

I think it is almost as bad a practice move (‘holding the angle’ pump drill) as stopping the club at impact to look and see if it is square. Block and hook city for both.

Tom Duke

Oct 20, 2014 at 8:24 pm

Hi CD..thanks for the comment. The “unloading” is a blend of the right elbow going from flexion into extension, the right forearm supinating (thumb goes to the right on the way down, as if you are turning a doorknob to the right), and the right wrist going from extension into flexion. Which means on the backswing, we need to fully load these movements just the opposite-hinge the wrist and elbow while the right forearm pronates (turns doorknob to the left). We try and eliminate pronation or any rolling of the forearms until after we have fully “advanced the shaft ” and released the the club head as described after impact.

Philip

Oct 20, 2014 at 2:59 pm

Jack Nicklaus said, “There is no such thing as a cast, just a slow lower half.” So, as golfers wrongly try to eliminate the “cast,” what they should really be doing is focusing on activating and accelerating their turning and thrusting system.

That is what I recently found for myself. I always questioned if I was casting whenever I hit fat, but what I find is that if I ensure I start from my lower body I don’t hit fat. I only “cast” per say if I throw my arms at the ball due to a set-up issue (usually too close to the ball) that prevents my natural trigger “push and pivot” from my legs.

I just have to keep reminding myself of that so that I don’t mess with my swing when I’m not sequencing properly.