Instruction

Which putting grip improves the average golfer’s alignments?

I’ve found that the most damaging flaw within a golfer’s putting is the breakdown of the lead wrist through impact. This flaw causes many more problems than anything else for the average golfer’s putting such as adding loft to the putter through impact, poor impact points on the face, incorrect pace control, loss of feel, loss of confidence and faulty impact alignments and subsequent aim. If I had to point to one move that will cause your putting stroke, confidence and ability to hole putts consistently to implode it would be this move.

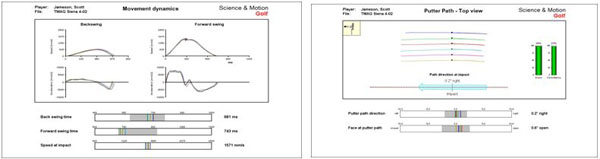

Within my putting academy, I use computer systems that can track motions of the body and putter. Advanced Motion Measurement’s 3D Motion Analysis System will track the motions of the wrists comparing them at address and impact, while the SAM Puttlab will track the motions of the putter head during impact.

Below, I have charted the performance characteristics in impact aim and the shaft angle at impact (which determines the impact alignments and the subsequent breakdown of the wrists) of 10 different grip. I’ve also tested players of each level and average their results within their handicap levels to give a general idea of what happens during the stroke. The handicap levels will be as follows: tour professional, scratch, 10, 18, 25 and 36.

The 10 Grips

- A “normal” putting grip

- The interlocking grip

- The overlapping grip

- The reverse-overlapping grip

- The reverse-overlapping grip with index finger extended

- The baseball grip

- The split baseball grip

- The left hand low grip

- The claw grip

- Bernhard Langer’s long left arm grip

- Strong rear hand grip

Desired impact alignments and terminology

The Goal at Impact is as flat forward wrist, a bent rear wrist and a neutral to slightly forward-leaning club shaft.

The Goal of Dynamic Loft During Impact is to preserve the static loft of the putter at impact so that the shaft angle is “0.”

Impact Aim is the direction that the putter face is aiming at impact. This factor determines 83 percent of the ball’s direction and can either be either open (O) or closed (C). If you cannot control the putter’s alignments during impact, then you will never be able to begin the ball on your intended line consistently. That means you will have a hard time making putts.

Shaft Lean is the amount of positive or negative “lean” of the club shaft at impact. If the putter shaft is leaning forward at impact, it will deloft (D) the putter’s static loft. If it is leaning backward at impact, it will add (A) to the putter’s static loft. We would like the putter to be relatively neutral at impact or very close to it. When the wrists are too active, the lead wrist breaks down adding loft to the putter during impact. This causes the ball to hop and skip, making feel and distance control inconsistent.

The Test

There is little change from address aim to impact aim in the tour professional.

One can derive several observations from the tour professional data above. Tour professionals, as you can imagine, aim the putter very close to where they are trying to at address, but not perfectly. At impact, any aiming deficiencies are accounted for. Thus, the ball leaves the blade on the chosen target line and this is the reason why these players are so good at controlling the ball’s starting direction. The putter’s shaft lean is basically neutral, helping the ball to leave the blade with the perfect roll characteristics using the loft designed into the putter naturally.

An impact alignment breakdown for the professional player does not happen too often. If anything, they ensure that they are not delofting the putter too actively during impact and do their best to make sure the loft of their putter remains relatively constant at the impact position. If they consistently deloft the putter through impact to a great degree, then they must add loft to their putters accordingly.

In regards to impact aim at the scratch level, there are not too many difference between each grip, however, when the “claw and Langer” grips are used, the shoulder rotation at impact seems to increase. When the shoulders are overactive during impact, it tends to cause the putter to close too rapidly. These players tend to move the ball back in their stance to accommodate this shoulder action.

When the “claw or Langer” grips are used the shoulders can become too overactive rotationally as shown above shutting down the blade at impact; thus, the ball position should be moved slightly back in the stance to accommodate.

As we examine the impact alignments and their effect on the effective loft of the putter, you will see that the scratch players, just like the tour professionals, must make sure that they are not leaning the shaft too far forward during impact and driving the ball into the ground.

When the putter shaft leans too far forward (as shown above) it can lead to the ball being driven into the ground through impact. Skidding and bouncing can result.

The only grip type that tends to consistently deloft the putter to an exaggerated degree on average is the split grip. This, in my opinion, is due to the shaft being set more forward at the address position, and why goflers such as Natalie Gulbis must make sure that they have more loft to their putters than most golfers. This added loft will correct for the extra shaft lean at impact and give these players a better chance for the ball to react favorably at impact.

As the level of handicap goes up, you will find that impact aim and impact alignments begin to suffer. This is why higher-handicap golfers are generally less consistent on the greens than the scratch players. These two factors cause a number of short birdie and par putts to be missed, driving up the scores of these players. From tee to green, the 10 handicap and the 18 handicap golfers are not too far off from one another, except for a few more loose shots by the 18-handicap player. But the number of missed up-and-downs goes up dramatically as these short putts are missed.

The impact aim of both levels of players shows that the “claw and the cross-handed grip” are the most accurate. This, in my opinion, is due to the fact that with the “claw” the rear forearm is more on-plane. That contributes to better putter face control since the path is usually better with this type of grip. When the rear forearm rides “high” or above the club shaft — as seen in the graphic below — the impact aim and the path are negatively affected. The “claw and cross-handed” place the rear forearm in a much more consistent position than the other normal putting grips, and this is what the data above shows in a number of players.

When the rear forearm is too high as shown above the impact aim of the putter tends to be closed and the ball misses left as a result.

From an impact alignment standpoint, these higher-handicap players are the ones who are just beginning to show some added hand action through impact, adding effective loft to their putters. When this occurs, the ball will tend to hop into the air at the start of its movement toward the hole, causing inconsistencies. This “jumping” causes many reactions of the ball to occur.

It is just this little bit of hand action and “skipping” of the ball that causes golfers to miss a number of very makeable putts: ones that the lower handicap players would tend to make. As you can see from the data, the best grip for reducing hand action in these players would be the Langer grip, with the left arm on the shaft itself. Golfers will find that if they have issues on short putts, they can very easily keep the putter shaft in a consistent position through impact with the Langer grip, allowing the ball to react the same way on putts of a certain length. I would suggest trying this grip on putts inside 12 feet if you have trouble maintaining a solid “rolling” of the ball off the start. The Langer grip is also good for golfers with the “yips,” which seem to affect this player grouping more than any other.

In my studies, the only real difference between the putting abilities of 25-handicap and 36-handicap golfers is the former group’s ability to monitor and control their hand action. These players have a slightly better time controlling their hand action than the 36-handicappers, thus any type of grip that allows them to monitor their hand action will work more effectively.

The two grip styles that control their impact aim are the two that allow them to monitor their hands more than any other:

- The reverse overlap with the rear index finger down the shaft

- The split grip.

The rear index finger is the most used finger on the human body, and its ability to sense and control what it is doing is one of the keys to putting at this level. As golfers extend this finger, they will find that the motions of the putter head are easily controlled. This is why the 25-handicap golfer has better success with this type of grip when it comes to impact aim. However, this rear finger grip can also lead to overuse. This is shown above by grip’s inability to help reduce impact alignment breakdown.

The reverse overlap grip with the rear finger down the shaft is one of the worst grips when it comes to preserving the static loft of the putter during impact. When the rear index finger is allowed to over control the motions of the putter, golfers will find that it will cause their impact alignment breakdown and add shaft lean at impact. When this occurs, golfers will not be able to control their speed and therefore will have little feel on the greens.

This explains why 25-handicap golfers can three-putt from just about any distance and at just about any time during the round. That said, it is easier for the 25 handicapper to reduce his number of three-putts in order to reduce his score than to work on making more short putts, the exact opposite case for lower-handicap golfers.

The 25-handicap golfer is guilty of adding too much loft to his putter when the reverse overlap with the index finger is extended grip is used.

When you examine the data tendencies in the 36-handicap golfer, you will see one thing in both categories: random data. This shows that this level of player has virtually little feeling or consistency in making the same type of stroke. This explains the golfer’s inability to control his or her speed or line on any type of putt.

One thing of note from the data, however, is that the “overlapping” grip — the same one generally used in the full swing — produced slightly better numbers for 36-handicap golfers. This is because this type of player uses this grip most often on the course, and generally has developed more feel with the grip than any other. Whenever these players are asked to change to a different putting grip, their feel tends to implode. Any grip other than the one they use most often can cause more inconsistent results.

These golfers must understand that the forward hand controls the rotation of the putter face and its alignments, while the rear hand and the bending of the rear wrist controls the shaft lean at impact and their subsequent feel. Anything other than a flat forward wrist and a bent rear wrist at impact will cause impact alignments and impact aim to be compromised. This is the most important lesson for the beginning golfer to understand and learn. Putting drills that involve each hand individually will help these players better understand the role of each hand during the putting stroke in order to have the proper alignments.

Conclusion

As with the full swing, different problems arise in putting for each handicap level of golfer. The higher the handicap, the less ball control the player has and the more important the understanding of the necessary impact alignments is for success. The better the player, the more important the proper aim of the putter is at impact. This is where a proper putter fitting and and properly weighted putter can really make a difference.

Higher-handicap golfers seem to three-putt more often because a lack of consistent shaft lean, which leads to poor feel and pace control. Lower-handicap golfers tend to miss makeable putts for pars and birdies because of poor impact alignments and aiming. Tour professionals understand subconsciously how to hit the ball where they want, and are able to put the shaft in the correct position more than lesser-talented golfers. That’s the main reason why they are more consistent.

As the data shows, different putting grips will work best for golfers of different ability levels, and it is necessary for golfers and their instructors to analyze their misses so that they can choose the correct grip. Sometimes direction is a problem, while other times feel is a problem. There are some grips that are better for directional control while others are better in controlling a golfer’s impact alignments. It is up to you to determine your problems and pick the right grip style accordingly.

Instruction

The Wedge Guy: Beating the yips into submission

There may be no more painful affliction in golf than the “yips” – those uncontrollable and maddening little nervous twitches that prevent you from making a decent stroke on short putts. If you’ve never had them, consider yourself very fortunate (or possibly just very young). But I can assure you that when your most treacherous and feared golf shot is not the 195 yard approach over water with a quartering headwind…not the extra tight fairway with water left and sand right…not the soft bunker shot to a downhill pin with water on the other side…No, when your most feared shot is the remaining 2- 4-foot putt after hitting a great approach, recovery or lag putt, it makes the game almost painful.

And I’ve been fighting the yips (again) for a while now. It’s a recurring nightmare that has haunted me most of my adult life. I even had the yips when I was in my 20s, but I’ve beat them into submission off and on most of my adult life. But just recently, that nasty virus came to life once again. My lag putting has been very good, but when I get over one of those “you should make this” length putts, the entire nervous system seems to go haywire. I make great practice strokes, and then the most pitiful short-stroke or jab at the ball you can imagine. Sheesh.

But I’m a traditionalist, and do not look toward the long putter, belly putter, cross-hand, claw or other variation as the solution. My approach is to beat those damn yips into submission some other way. Here’s what I’m doing that is working pretty well, and I offer it to all of you who might have a similar affliction on the greens.

When you are over a short putt, forget the practice strokes…you want your natural eye-hand coordination to be unhindered by mechanics. Address your putt and take a good look at the hole, and back to the putter to ensure good alignment. Lighten your right hand grip on the putter and make sure that only the fingertips are in contact with the grip, to prevent you from getting to tight.

Then, take a long, long look at the hole to fill your entire mind and senses with the target. When you bring your head/eyes back to the ball, try to make a smooth, immediate move right into your backstroke — not even a second pause — and then let your hands and putter track right back together right back to where you were looking — the HOLE! Seeing the putter make contact with the ball, preferably even the forward edge of the ball – the side near the hole.

For me, this is working, but I am asking all of you to chime in with your own “home remedies” for the most aggravating and senseless of all golf maladies. It never hurts to have more to fall back on!

Instruction

Looking for a good golf instructor? Use this checklist

Over the last couple of decades, golf has become much more science-based. We measure swing speed, smash factor, angle of attack, strokes gained, and many other metrics that can really help golfers improve. But I often wonder if the advancement of golf’s “hard” sciences comes at the expense of the “soft” sciences.

Take, for example, golf instruction. Good golf instruction requires understanding swing mechanics and ball flight. But let’s take that as a given for PGA instructors. The other factors that make an instructor effective can be evaluated by social science, rather than launch monitors.

If you are a recreational golfer looking for a golf instructor, here are my top three points to consider.

1. Cultural mindset

What is “cultural mindset? To social scientists, it means whether a culture of genius or a culture of learning exists. In a golf instruction context, that may mean whether the teacher communicates a message that golf ability is something innate (you either have it or you don’t), or whether golf ability is something that can be learned. You want the latter!

It may sound obvious to suggest that you find a golf instructor who thinks you can improve, but my research suggests that it isn’t a given. In a large sample study of golf instructors, I found that when it came to recreational golfers, there was a wide range of belief systems. Some instructors strongly believed recreational golfers could improve through lessons. while others strongly believed they could not. And those beliefs manifested in the instructor’s feedback given to a student and the culture created for players.

2. Coping and self-modeling can beat role-modeling

Swing analysis technology is often preloaded with swings of PGA and LPGA Tour players. The swings of elite players are intended to be used for comparative purposes with golfers taking lessons. What social science tells us is that for novice and non-expert golfers, comparing swings to tour professionals can have the opposite effect of that intended. If you fit into the novice or non-expert category of golfer, you will learn more and be more motivated to change if you see yourself making a ‘better’ swing (self-modeling) or seeing your swing compared to a similar other (a coping model). Stay away from instructors who want to compare your swing with that of a tour player.

3. Learning theory basics

It is not a sexy selling point, but learning is a process, and that process is incremental – particularly for recreational adult players. Social science helps us understand this element of golf instruction. A good instructor will take learning slowly. He or she will give you just about enough information that challenges you, but is still manageable. The artful instructor will take time to decide what that one or two learning points are before jumping in to make full-scale swing changes. If the instructor moves too fast, you will probably leave the lesson with an arm’s length of swing thoughts and not really know which to focus on.

As an instructor, I develop a priority list of changes I want to make in a player’s technique. We then patiently and gradually work through that list. Beware of instructors who give you more than you can chew.

So if you are in the market for golf instruction, I encourage you to look beyond the X’s and O’s to find the right match!

Instruction

What Lottie Woad’s stunning debut win teaches every golfer

Most pros take months, even years, to win their first tournament. Lottie Woad needed exactly four days.

The 21-year-old from Surrey shot 21-under 267 at Dundonald Links to win the ISPS Handa Women’s Scottish Open by three shots — in her very first event as a professional. She’s only the third player in LPGA history to accomplish this feat, joining Rose Zhang (2023) and Beverly Hanson (1951).

But here’s what caught my attention as a coach: Woad didn’t win through miraculous putting or bombing 300-yard drives. She won through relentless precision and unshakeable composure. After watching her performance unfold, I’m convinced every golfer — from weekend warriors to scratch players — can steal pages from her playbook.

Precision Beats Power (And It’s Not Even Close)

Forget the driving contests. Woad proved that finding greens matters more than finding distance.

What Woad did:

• Hit it straight, hit it solid, give yourself chances

• Aimed for the fat parts of greens instead of chasing pins

• Let her putting do the talking after hitting safe targets

• As she said, “Everyone was chasing me today, and managed to maintain the lead and played really nicely down the stretch and hit a lot of good shots”

Why most golfers mess this up:

• They see a pin tucked behind a bunker and grab one more club to “go right at it”

• Distance becomes more important than accuracy

• They try to be heroic instead of smart

ACTION ITEM: For your next 10 rounds, aim for the center of every green regardless of pin position. Track your greens in regulation and watch your scores drop before your swing changes.

The Putter That Stayed Cool Under Fire

Woad started the final round two shots clear and immediately applied pressure with birdies at the 2nd and 3rd holes. When South Korea’s Hyo Joo Kim mounted a charge and reached 20-under with a birdie at the 14th, Woad didn’t panic.

How she responded to pressure:

• Fired back with consecutive birdies at the 13th and 14th

• Watched Kim stumble with back-to-back bogeys

• Capped it with her fifth birdie of the day at the par-5 18th

• Stayed patient when others pressed, pressed when others cracked

What amateurs do wrong:

• Get conservative when they should be aggressive

• Try to force magic when steady play would win

• Panic when someone else makes a move

ACTION ITEM: Practice your 3-6 foot putts for 15 minutes after every range session. Woad’s putting wasn’t spectacular—it was reliable. Make the putts you should make.

Course Management 101: Play Your Game, Not the Course’s Game

Woad admitted she couldn’t see many scoreboards during the final round, but it didn’t matter. She stuck to her game plan regardless of what others were doing.

Her mental approach:

• Focused on her process, not the competition

• Drew on past pressure situations (Augusta National Women’s Amateur win)

• As she said, “That was the biggest tournament I played in at the time and was kind of my big win. So definitely felt the pressure of it more there, and I felt like all those experiences helped me with this”

Her physical execution:

• 270-yard drives (nothing flashy)

• Methodical iron play

• Steady putting

• Everything effective, nothing spectacular

ACTION ITEM: Create a yardage book for your home course. Know your distances to every pin, every hazard, every landing area. Stick to your plan no matter what your playing partners are doing.

Mental Toughness Isn’t Born, It’s Built

The most impressive part of Woad’s win? She genuinely didn’t expect it: “I definitely wasn’t expecting to win my first event as a pro, but I knew I was playing well, and I was hoping to contend.”

Her winning mindset:

• Didn’t put winning pressure on herself

• Focused on playing well and contending

• Made winning a byproduct of a good process

• Built confidence through recent experiences:

- Won the Women’s Irish Open as an amateur

- Missed a playoff by one shot at the Evian Championship

- Each experience prepared her for the next

What this means for you:

• Stop trying to shoot career rounds every time you tee up

• Focus on executing your pre-shot routine

• Commit to every shot

• Stay present in the moment

ACTION ITEM: Before each round, set process goals instead of score goals. Example: “I will take three practice swings before every shot” or “I will pick a specific target for every shot.” Let your score be the result, not the focus.

The Real Lesson

Woad collected $300,000 for her first professional victory, but the real prize was proving that fundamentals still work at golf’s highest level. She didn’t reinvent the game — she simply executed the basics better than everyone else that week.

The fundamentals that won:

• Hit more fairways

• Find more greens

• Make the putts you should make

• Stay patient under pressure

That’s something every golfer can do, regardless of handicap. Lottie Woad just showed us it’s still the winning formula.

FINAL ACTION ITEM: Pick one of the four action items above and commit to it for the next month. Master one fundamental before moving to the next. That’s how champions are built.

PGA Professional Brendon Elliott is an award-winning coach and golf writer. You can check out his writing work and learn more about him by visiting BEAGOLFER.golf and OneMoreRollGolf.com. Also, check out “The Starter” on RG.org each Monday.

Editor’s note: Brendon shares his nearly 30 years of experience in the game with GolfWRX readers through his ongoing tip series. He looks forward to providing valuable insights and advice to help golfers improve their game. Stay tuned for more Tips!

Pingback: http://www.golfwrx.com/162633/which-putting-grip-improves-the-average-golfers-alignments/ | athletic golfer

joe sixpack

Mar 6, 2014 at 12:29 pm

I second hebron1427’s comment. Without knowing your sample size or the standard deviations there’s no way to know if your data is statistically significant.

For example, you advised Gabe to try a left hand low grip, presumably because that grip has the closest to neutral average impact aim (0.7 closed vs. 1.0-2.9 for other grips) for 18 handicap players. But what if that 0.7 figure were based on only 5 players who ranged from 3 degrees open to 5 degrees closed? If that were the case, this wouldn’t be meaningful at all.

Statistics can look powerful but without sample size and standard deviation information there is no way to tell if something like this has any validity.

Tom Stickney

Mar 6, 2014 at 9:03 pm

Understand totally however I’d advise you have fun with this article and experiment to find your own best grip.

paul

Mar 4, 2014 at 2:04 pm

I would love to see an article on how different grips for full swings makes a difference. I use a baseball style grip (smallerish hands). One plane swing and hit it with a pull. And always wondered if there was a connection. Approximately 14 handicap.

Tom Stickney

Mar 4, 2014 at 5:35 pm

Might do that. Thx.

Gabe

Mar 4, 2014 at 1:40 pm

I recently had a SAM putter fitting and the results were as follows:

Face Aim: 0.7 open

Shaft Lean: 2.0 add loft

I’m around an 18 hcp but have only been playing for 2 years. I use a traditional grip, how do I apply your data to determine a possibly better putter grip?

Tom Stickney

Mar 4, 2014 at 5:35 pm

Left hand low

Sky

Mar 3, 2014 at 9:20 pm

In general, do you want to hit up or down on a putt?

Tom Stickney

Mar 3, 2014 at 10:52 pm

Up always

hebron1427

Mar 3, 2014 at 12:36 pm

while this is interesting, it’s not particularly helpful without statistical data. did you do any statistical analysis and come up with any standard deviations on impact aim for the various handicaps? for a 36 handicap, all of these could be within the standard error.

Tom Stickney

Mar 3, 2014 at 10:54 pm

Get what you’re asking mike but this is just a general analysis of what the “average” golfer needs to experiment with in order to fix their issues