Instruction

Biomechanics and their affect on swing plane

Every golfer is unique, and this individuality has to do with biomechanics. It’s a well known fact that many scientists and biomechanists have understood for many years, however, it is something that many golf professionals have still not accepted.

There are many methods and styles of teaching in our business and the variations are endless: Stack and Tilt v. Jimmy Ballard, Sean Foley v. Hank Haney and on and on. I’m NOT saying for one second that any of these great instructors are wrong, because they have all been immensely successful and the beautiful thing is that they are all correct in their method. The problem is that certain methods are not right for everyone. The differences in each person’s biomechanics is what this article is about, more specifically how biomechanics relates to swing plane.

Everything I will refer to in this article has been proven by science and by golf biomechanists, and is taken directly from BioSwing Dynamics, which was developed by Mike Adams and E.A. Tischler. I am lucky enough to have these two as mentors during my BioSwing Dynamics certification, and I would like to thank them immensely for their help in my growth as an instructor and for their help in editing this article.

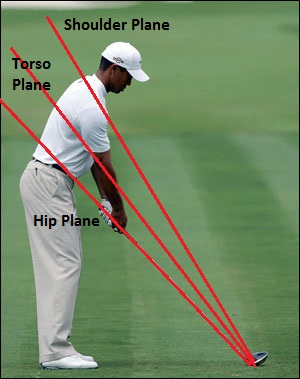

There are three different top of the backswing planes and three different downswing planes. At the top of the backswing, the golfer can achieve a position that aligns the lead arm either above the shoulder line (high-plane), through the shoulder line (mid-plane) or below the shoulder line (low-plane). This is shown explicitly in the picture above of Matt Kuchar, Tiger Woods and Jim Furyk when they are at the top of their backswing. During the downswing the golfer will deliver the club along the hip plane (also known as the shaft plane), the torso plane or the shoulder plane.

The backswing plane and downswing plane may vary based upon the two tests you will be introduced to in this article. I will also refer to PGA Tour players as an example, which were tested by Mike Adams during the research portion of BioSwing Dynamics. Just like there are many different methods of teaching, there are many different “looks” of a golfer: David Toms, Martin Kaymer, Charl Schwartzel, Hunter Mahan, Ernie Els, etc. By understanding these simple principles, you will better understand how your biomechanics will affect your individual swing. So, let’s get started.

Needless to say, the backswing is an important part of the golf swing because it will help prepare the swing for proper use of leverage in the swing. It also positions you for a well-executed transition into the delivery slot during the downswing. In order to test what backswing plane fits your body, you need to perform the following test (you will need a partner):

- Stand up and hold your arms stretched out at shoulder height.

- Have someone measure your wingspan from finger tips on the right hand to finger tips on the left hand.

- Have your helper measure your height.

- If your wingspan and height are the same lengths, then you will have a top of the backswing position that aligns the lead arm through your trailing shoulder. This is much like what is taught in one-plane theories.

- As the wingspan becomes longer than the height, the lead arm will elevate more above the shoulder line into what has been described as a two-plane position at the top of the backswing.

- If the wingspan is shorter than the height, the lead arm will align below the shoulder line at the top of the backswing in what is commonly called a flat backswing.

Keep in mind that that there is a range in which the lead arm will be set at the top of the backswing. If the wingspan is, say, 4 inches shorter than the height, the lead arm will set very low across the chest and below the shoulder line. If the wingspan is, say, 4 inches longer than the height, then the lead arm will set well above the shoulder line into a high two-plane type of alignment.

Simply put, the alignment of the lead arm in relations to the shoulder line at the top of the backstroke needs to match the relationship between the length of the wingspan and the height of the golfer. Please refer to the pictures below as a reference to measuring wingspan and height.

Now, how the golfer swings to that top-set position will vary from golfer to golfer. For example, some golfers will swing inside and then elevate upward like Sam Snead, Bruce Lietzke and Matt Kuchar. Others will swing up along an outside path, like Fred Couples and Lee Trevino, and then loop the club into the top-set before transitioning into the slot. Then there will be golfers that seem to swing up the same path they will eventually slot along during the downswing. This is based upon how the arms fold in the backswing. There will be a follow up article explaining the different ways a person can fold the trail arm and how it relates to the backswing.

Examples of Hip-Planers in the takeaway are Matt Kuchar and Jason Dufner. Examples of Torso-Planers in the takeaway are Hunter Mahan or Rory McIlroy. Examples of Shoulder-Planers in the takeaway are Charl Schwartzel and Martin Kaymer. Each of these players are excellent ball strikers, but they each have their own individual ways of swinging the golf club that is based upon their body.

How do you test to see what downswing plane fits your body’s mechanics? To figure that out, measure your forearm from the middle knuckle to the elbow and then measure the upper arm from the elbow to the shoulder socket. Please refer to the pictures above that show how this is measured. Based upon their relationship, you will swing on one of the three swing planes we discussed earlier. Here are your three options:

- Hip-Plane Downswing: The distance from the middle knuckle to forearm is SHORTER than the distance from the elbow to the shoulder socket.

- Torso-Plane Downswing: The distance from the middle knuckle to forearm is EQUAL TO the distance from the elbow to the shoulder socket.

- Shoulder-Plane Downswing: The distance from the middle knuckle to forearm is LONGER than the distance from the elbow to the shoulder socket.

The easiest way to think about this is that if the forearm is longer than the upper arm, the hands will ride higher and farther out, so they should come down on a steeper plane than if they were shorter. If the upper arm is longer and the forearm is shorter, then the hands will ride lower and closer to the body. That will produce a more shallow delivery plane. Here are some more examples of PGA Tour players and how they swing.

- Hip-Plane Downswing: Heath Slocum

- Torso-Plane Downswing: Ernie Els, Hunter Mahan, Adam Scott

- Shoulder-Plane Downswing: Martin Kaymer, Camilo Villegas, John Senden

Martin Kaymer is a perfect example of how getting out of your proper swing plane can affect your performance. In 2010, Martin was playing the best golf of his career. He had won the PGA Championship, and shortly after his runner-up finish in the 2011 WGC-Accenture Match Play Championship he became the No. 1-ranked player in the Official World Golf Rankings. He lost the No. 1 spot 8 weeks after to Lee Westwood.

With his decline in the world rankings, we can see definite changes in his swing that have proven to be mismatched to his body mechanics. When he won, Kaymer was swinging the club down on the shoulder plane like he tests out to be. He and his instructor decided to work on getting the club lower and closer, delivering it down the hip-plane, which is how most instructors at the time thought the golf swing should be swung. He quickly fell in the rankings until late 2012, when he went back to working on retooling his swing. In studying his swing we have found that his swing plane is getting closer to where it was in the 2009 and 2010 seasons when he was playing his best golf. And guess what? We are starting to see the name Martin Kaymer on leaderboards again.

Matching the planes of both the backswing and downswing with the appropriate hip movement and wrist hinge will help golfers tremendously. Proper wrist hinge and the matching of a golfer’s hip movement to his or her setup will be discussed in future articles, as I want you to properly understand this first. Realizing that your individual body mechanics can and will influence the golf swing is the first step in a much bigger picture that will take your game to new levels.

Instruction

The Wedge Guy: Beating the yips into submission

There may be no more painful affliction in golf than the “yips” – those uncontrollable and maddening little nervous twitches that prevent you from making a decent stroke on short putts. If you’ve never had them, consider yourself very fortunate (or possibly just very young). But I can assure you that when your most treacherous and feared golf shot is not the 195 yard approach over water with a quartering headwind…not the extra tight fairway with water left and sand right…not the soft bunker shot to a downhill pin with water on the other side…No, when your most feared shot is the remaining 2- 4-foot putt after hitting a great approach, recovery or lag putt, it makes the game almost painful.

And I’ve been fighting the yips (again) for a while now. It’s a recurring nightmare that has haunted me most of my adult life. I even had the yips when I was in my 20s, but I’ve beat them into submission off and on most of my adult life. But just recently, that nasty virus came to life once again. My lag putting has been very good, but when I get over one of those “you should make this” length putts, the entire nervous system seems to go haywire. I make great practice strokes, and then the most pitiful short-stroke or jab at the ball you can imagine. Sheesh.

But I’m a traditionalist, and do not look toward the long putter, belly putter, cross-hand, claw or other variation as the solution. My approach is to beat those damn yips into submission some other way. Here’s what I’m doing that is working pretty well, and I offer it to all of you who might have a similar affliction on the greens.

When you are over a short putt, forget the practice strokes…you want your natural eye-hand coordination to be unhindered by mechanics. Address your putt and take a good look at the hole, and back to the putter to ensure good alignment. Lighten your right hand grip on the putter and make sure that only the fingertips are in contact with the grip, to prevent you from getting to tight.

Then, take a long, long look at the hole to fill your entire mind and senses with the target. When you bring your head/eyes back to the ball, try to make a smooth, immediate move right into your backstroke — not even a second pause — and then let your hands and putter track right back together right back to where you were looking — the HOLE! Seeing the putter make contact with the ball, preferably even the forward edge of the ball – the side near the hole.

For me, this is working, but I am asking all of you to chime in with your own “home remedies” for the most aggravating and senseless of all golf maladies. It never hurts to have more to fall back on!

Instruction

Looking for a good golf instructor? Use this checklist

Over the last couple of decades, golf has become much more science-based. We measure swing speed, smash factor, angle of attack, strokes gained, and many other metrics that can really help golfers improve. But I often wonder if the advancement of golf’s “hard” sciences comes at the expense of the “soft” sciences.

Take, for example, golf instruction. Good golf instruction requires understanding swing mechanics and ball flight. But let’s take that as a given for PGA instructors. The other factors that make an instructor effective can be evaluated by social science, rather than launch monitors.

If you are a recreational golfer looking for a golf instructor, here are my top three points to consider.

1. Cultural mindset

What is “cultural mindset? To social scientists, it means whether a culture of genius or a culture of learning exists. In a golf instruction context, that may mean whether the teacher communicates a message that golf ability is something innate (you either have it or you don’t), or whether golf ability is something that can be learned. You want the latter!

It may sound obvious to suggest that you find a golf instructor who thinks you can improve, but my research suggests that it isn’t a given. In a large sample study of golf instructors, I found that when it came to recreational golfers, there was a wide range of belief systems. Some instructors strongly believed recreational golfers could improve through lessons. while others strongly believed they could not. And those beliefs manifested in the instructor’s feedback given to a student and the culture created for players.

2. Coping and self-modeling can beat role-modeling

Swing analysis technology is often preloaded with swings of PGA and LPGA Tour players. The swings of elite players are intended to be used for comparative purposes with golfers taking lessons. What social science tells us is that for novice and non-expert golfers, comparing swings to tour professionals can have the opposite effect of that intended. If you fit into the novice or non-expert category of golfer, you will learn more and be more motivated to change if you see yourself making a ‘better’ swing (self-modeling) or seeing your swing compared to a similar other (a coping model). Stay away from instructors who want to compare your swing with that of a tour player.

3. Learning theory basics

It is not a sexy selling point, but learning is a process, and that process is incremental – particularly for recreational adult players. Social science helps us understand this element of golf instruction. A good instructor will take learning slowly. He or she will give you just about enough information that challenges you, but is still manageable. The artful instructor will take time to decide what that one or two learning points are before jumping in to make full-scale swing changes. If the instructor moves too fast, you will probably leave the lesson with an arm’s length of swing thoughts and not really know which to focus on.

As an instructor, I develop a priority list of changes I want to make in a player’s technique. We then patiently and gradually work through that list. Beware of instructors who give you more than you can chew.

So if you are in the market for golf instruction, I encourage you to look beyond the X’s and O’s to find the right match!

Instruction

What Lottie Woad’s stunning debut win teaches every golfer

Most pros take months, even years, to win their first tournament. Lottie Woad needed exactly four days.

The 21-year-old from Surrey shot 21-under 267 at Dundonald Links to win the ISPS Handa Women’s Scottish Open by three shots — in her very first event as a professional. She’s only the third player in LPGA history to accomplish this feat, joining Rose Zhang (2023) and Beverly Hanson (1951).

But here’s what caught my attention as a coach: Woad didn’t win through miraculous putting or bombing 300-yard drives. She won through relentless precision and unshakeable composure. After watching her performance unfold, I’m convinced every golfer — from weekend warriors to scratch players — can steal pages from her playbook.

Precision Beats Power (And It’s Not Even Close)

Forget the driving contests. Woad proved that finding greens matters more than finding distance.

What Woad did:

• Hit it straight, hit it solid, give yourself chances

• Aimed for the fat parts of greens instead of chasing pins

• Let her putting do the talking after hitting safe targets

• As she said, “Everyone was chasing me today, and managed to maintain the lead and played really nicely down the stretch and hit a lot of good shots”

Why most golfers mess this up:

• They see a pin tucked behind a bunker and grab one more club to “go right at it”

• Distance becomes more important than accuracy

• They try to be heroic instead of smart

ACTION ITEM: For your next 10 rounds, aim for the center of every green regardless of pin position. Track your greens in regulation and watch your scores drop before your swing changes.

The Putter That Stayed Cool Under Fire

Woad started the final round two shots clear and immediately applied pressure with birdies at the 2nd and 3rd holes. When South Korea’s Hyo Joo Kim mounted a charge and reached 20-under with a birdie at the 14th, Woad didn’t panic.

How she responded to pressure:

• Fired back with consecutive birdies at the 13th and 14th

• Watched Kim stumble with back-to-back bogeys

• Capped it with her fifth birdie of the day at the par-5 18th

• Stayed patient when others pressed, pressed when others cracked

What amateurs do wrong:

• Get conservative when they should be aggressive

• Try to force magic when steady play would win

• Panic when someone else makes a move

ACTION ITEM: Practice your 3-6 foot putts for 15 minutes after every range session. Woad’s putting wasn’t spectacular—it was reliable. Make the putts you should make.

Course Management 101: Play Your Game, Not the Course’s Game

Woad admitted she couldn’t see many scoreboards during the final round, but it didn’t matter. She stuck to her game plan regardless of what others were doing.

Her mental approach:

• Focused on her process, not the competition

• Drew on past pressure situations (Augusta National Women’s Amateur win)

• As she said, “That was the biggest tournament I played in at the time and was kind of my big win. So definitely felt the pressure of it more there, and I felt like all those experiences helped me with this”

Her physical execution:

• 270-yard drives (nothing flashy)

• Methodical iron play

• Steady putting

• Everything effective, nothing spectacular

ACTION ITEM: Create a yardage book for your home course. Know your distances to every pin, every hazard, every landing area. Stick to your plan no matter what your playing partners are doing.

Mental Toughness Isn’t Born, It’s Built

The most impressive part of Woad’s win? She genuinely didn’t expect it: “I definitely wasn’t expecting to win my first event as a pro, but I knew I was playing well, and I was hoping to contend.”

Her winning mindset:

• Didn’t put winning pressure on herself

• Focused on playing well and contending

• Made winning a byproduct of a good process

• Built confidence through recent experiences:

- Won the Women’s Irish Open as an amateur

- Missed a playoff by one shot at the Evian Championship

- Each experience prepared her for the next

What this means for you:

• Stop trying to shoot career rounds every time you tee up

• Focus on executing your pre-shot routine

• Commit to every shot

• Stay present in the moment

ACTION ITEM: Before each round, set process goals instead of score goals. Example: “I will take three practice swings before every shot” or “I will pick a specific target for every shot.” Let your score be the result, not the focus.

The Real Lesson

Woad collected $300,000 for her first professional victory, but the real prize was proving that fundamentals still work at golf’s highest level. She didn’t reinvent the game — she simply executed the basics better than everyone else that week.

The fundamentals that won:

• Hit more fairways

• Find more greens

• Make the putts you should make

• Stay patient under pressure

That’s something every golfer can do, regardless of handicap. Lottie Woad just showed us it’s still the winning formula.

FINAL ACTION ITEM: Pick one of the four action items above and commit to it for the next month. Master one fundamental before moving to the next. That’s how champions are built.

PGA Professional Brendon Elliott is an award-winning coach and golf writer. You can check out his writing work and learn more about him by visiting BEAGOLFER.golf and OneMoreRollGolf.com. Also, check out “The Starter” on RG.org each Monday.

Editor’s note: Brendon shares his nearly 30 years of experience in the game with GolfWRX readers through his ongoing tip series. He looks forward to providing valuable insights and advice to help golfers improve their game. Stay tuned for more Tips!

Pingback: 7 Best Golf Swing Analysis Apps: iPhone, Android, & Free – Golf Span – outgolfed.com

Jay Ferguson

Jun 15, 2022 at 5:23 pm

This sounds like a lot of bro science

Wilson

Dec 5, 2016 at 7:13 pm

Hey Michael, just found this article. Very interesting stuff. What plane would you say Jason Dufner comes down on?

Thanks!

Mj

Nov 25, 2017 at 1:16 pm

What about the hand plane. ? The most important plane imo.

If this is bio mechanical the club should not even be in the picture. Agreed?

Thank you for this article. Just found it

Mbwa Kali Sana

Aug 16, 2016 at 8:58 am

In m’y opinion ,you fin d your own swing by yourself ,swinging in front OF a mirror ,and checking THE positions ,together with measuring THE speed OF THE clubface with a swing speed radar .

By trial and error ,you discover what suits you best .

Toby Zabel

Jun 23, 2015 at 8:13 pm

Michael,

So does this mean that shoulder planers are more suited to hitting cuts and taking large divots, and hip planers are more suited to hitting draws and taking smaller divots, and torso planers are in between?

kyle

Nov 19, 2014 at 10:31 pm

I feel dumb but if my wingspan is greater than height it means?

Ewan S Fallon

Nov 17, 2014 at 3:57 pm

Instead of getting measured etc. why not just try different swing planes, and adopt the one which feels and scores best? Amen!

Joe

Sep 17, 2015 at 8:56 am

I guess if its that easy for you to switch planes you can do that. For me any change is going to take a lot of work.

woody

Jul 27, 2014 at 11:16 am

Hi, and thank you for a very interesting article but I am now really confused, my wingspan is 3 inches longer than mu height but my forearm is 1 inch shorter than my upper arm, do these findings contradict each other thereby leaving me with no option but to take up cricket yuk!!!!

woody

Jul 27, 2014 at 11:14 am

Hi, very interesting article but I am now really confused, my wingspan is 3 inches longer than mu height but my forearm is 1 inch shorter than my upper arm, do these findings contradict each other thereby leaving me with no option but to take up cricket yuk!!!!

Gary

May 5, 2014 at 11:08 am

Mike,

I’ve read the article in Golf Magazine, and it contradicts what you’re saying. The article doesn’t mention anything about measuring your wingspan and forearm. It tells you to look in a mirror and check your elbow position when it starts to fold. According to the article I’m a torso swing plane and by my measurements I have a shoulder plane swing. My wingspan is the same as my height and my forearm is longer than my upper arm. Could you tell me which is correct.

Michael Wheeler

May 16, 2014 at 2:36 pm

Gary, that is a different test. The BioSwing Dynamic certification has several tests and these three (right arm folding test, wingspan test, and forearm/upper arm test) are only a few of them. The wingspan test tells us if the golfer should be more rotary or lateral in their motion, and the forearm to upper arm measurement explains which plane you should use in the downswing. The test that Mike and EA are talking about in GOLF Magazine is for backswing and how you should release the golf club. If you test out to be a torso planer with that test moving the hands to the right (the GOLF Magazine article) and your forearm is longer (shoulder plane downswing) your body will want to swing the club back on the torso plane and then down on the shoulder plane. There are nine different combinations, but that would be your pattern if you test out to be a “side on” golfer and the forearm is longer than the left. I am that pattern as well for example.

Don’t confuse the two tests. Mike and EA wrote an article last year about the wingspan and forearm tests, and the current article they wrote in May 2014 is about backswing and using the proper release to match your biomechanics.

If you have any other questions about your measurements from Mike’s article and the wingspan and forearm tests please feel free to shoot me an email. My contact information is on my website (www.michaelwheelergolf.com).

Paul

Apr 30, 2014 at 6:23 pm

Great article Michael.

My wingspan is 6ft2, my height is 6ft4. So I should be a hip planer.

However, my knuckle to elbow is LONGER than my elbow to shoulder just slightly (39.5mm to 37.5mm), which says I should be a shoulder planer.

Where should I be?

Thanks

Paul

EA Tischler

May 1, 2014 at 9:19 pm

Paul, the wingspan being 2 inches shorter than your height will make the most efficient alignment of the lead arm in what we call low mid-track or high-low track. It depends on how much rounding forward you have in your address posture. Keep in mind that the tests narrow down the range in which the lead arm will be aligned at the top of the backswing. As a general description that means the lead arm will swing across your chest and through the lower part of your shoulder line. Your forearm being longer than you lead arm by 2mm would make you a torso-planer while slotting during the downswing. It would slot above the middle of the torso-plane zone. So, keep in mind that one test is for the track during the backswing and the other is for the track during delivery.

GolferX

Apr 24, 2014 at 4:11 pm

Having a baseball background, I can understand that each one of us has a swing that is going to be different; now that is proven by this article describing the use of biomechanics. However, what biomechanics can’t tell us is what if anything can be done if we are the outlier in the group. What if we are the one exception to the rule? That is where practice and getting to know your swing ala Hogan or Moe Norman. When I played baseball, we still used wooden bats and I found that by simply lowering my hands about two inches, I was able to get to those fastballs that were my weakness, it simply took the willingness to learn about myself and my swing.

Kirk

Apr 24, 2014 at 3:05 pm

Great article! I just want to be clear about the height measurement and if it should be taken in golf shoes, or barefoot? Again, great article.

Tyler

Apr 24, 2014 at 11:17 am

Great Article Mike. I was trying to locate the Mike Adams article on the golf magazine website and had no luck. Do you know the name of the article?

Michael Wheeler

Apr 24, 2014 at 12:03 pm

It may not be online yet, as it is in stores in the current May issue of GOLF Magazine. Tiger is on the cover…

AIPM

Apr 23, 2014 at 2:06 pm

Fantastic article. Definitely looking forward to the second part.

A few questions though. Would this make any difference in putting, or is everything too stationary and the movement too small to have any real effect? I’m sure short game and bunker play could be affected by this though, so will this be addressed in future articles? Finally, are all three downswing planes able to have club path adjusted in order to shape shots both ways as well as attack angle, or only the torso plane?

Greg

Apr 23, 2014 at 11:32 am

Michael,

Great article. How far off should the two measurements be to bump you into the outside categories? I’m 72 inches tall with a 71 inch wing span which doesn’t seem like much difference. My forearms however are a full 2 inches shorter so that seems like I clearly need to be on the hip plane.

Also is there anyway to find a certified instructor locally (Richmond, VA)?

Michael Wheeler

Apr 23, 2014 at 8:27 pm

I would take a ride up to visit Mike Adams if I were you. He is in southern NY, and not crazy far from Richmond. You will get a lot of great information from the trip and would be well worth it. There are also several instructors in Baltimore. I’ll see if there are more close to you, but a trip to Mike would be well worth it if you can get in with him!

Jordan V

Apr 23, 2014 at 8:00 am

Great article. Can’t wait for the follow-up articles. I have always struggled to find a comfortable backswing. My measurements were about 2″ longer with the wingspan and 2″ longer with the forearm. I have always tried to keep my backswing and downswing plane lower, and I see now that I have been fighting my biomechanics. One question is with 2″ longer on both measurements, would I be a low shoulder plane, or just above the torso plane?

Michael Wheeler

Apr 23, 2014 at 8:25 pm

There is no need for a follow up article… Mike Adams and EA Tischler recently wrote a great article in GOLF Magazine this month, which is the cover story with Tiger on the cover. Make sure to check out that article; a lot of great information!

To answer your specific question Jordan, since your forearm is 2″ longer, than you will be a shoulder planer. You will be pretty close to the top line. I am the same as you, as my forearm is 2″ longer also. That would definitely be why you will struggle more in a lower plane. Glad I could help…

Tyler

Apr 24, 2014 at 11:21 am

Great Article Mike. What is the name of the article as I cannot find it on the Golf magazine websire.

JD

Apr 23, 2014 at 7:41 am

Hi. Very good article and as a teaching pro I understand the importance and relevance of these measurements. Although all the examples are great with players matching their measurements what about the opposite?

Are there successful players that have been tested that have swung the club on a plane that does not match their measurements. I think of a few tour players who’s golf swings have changed over the years but their physical measurements have not. Tiger being one example.

Josh

Apr 23, 2014 at 7:36 am

As with all new golf instruction theories, I tend to first be skeptical. Michael, this is an interesting read, but all you did was give us some rules for choosing a swing plane without any bio mechanical proof as to why. Other than saying that someone else did the research, we are all certified, here are a few pro names that match our research as proof.

Why are these rules as such, biomechanically speaking? How were the studies done to come to these conclusions? Is there any room for bending these rules when it comes to my backswing and downswing plane?

Apologies if I sound confrontational, but too many times golf instructors have the ‘solution’ to everything, and I think as golfers we need to question a little more instead of following blindly and jumping from trend to trend.

Tony

Apr 23, 2014 at 1:50 pm

I’m in the same boat as Josh. Would love to see a follow up here.

ParHunter

Apr 23, 2014 at 4:16 pm

I would like to see some explanation as well. I find it non-intuitive that long arms should lead to a more upright backswing. Isn’t it the case that a longer club (e.g. the driver) leads to a flatter swing than with a shorter club (e.g. A wedge). So I would expect the opposite, that long arms lead to a flatter swing and short one to a more upright.

Philip

Apr 23, 2014 at 5:24 pm

Except that in golf a lot of things tend to be opposite of what common sense dictates. Which I suspect is the result of the golf swing being the combination of multiple gear and lever actions via our body and limbs.

Dave

Apr 30, 2014 at 8:19 am

I had exactly the same thought. With longer arms, wouldn’t the arms start at address further from the body and then work around the spine on a flatter plane?

TheFightingEdFioris

Apr 23, 2014 at 11:06 pm

There is a great (but lengthy) video on YouTube of Mike Adams speaking, and explaining this theory, at the PGA Show. In my opinion it’s a must-watch.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fZz06H-3SSA

Stretch

Jun 2, 2014 at 4:32 pm

Just watched it. A must watch as well as a pdf available,

http://mikeadamsgolf.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Cover_Swing_Tracking1.pdf

EA Tischler

May 1, 2014 at 11:51 pm

Josh, many professional golfers have won using techniques that fail to fit their body mechanics. They are talented enough, and as long as they can manage ball flight, scramble well and have great strokes gained numbers then they can win. However we see hoards of injuries in golfers, including professionals that are extremely fit, when they develop swings that fail to match their biomechanical design. Let me also make it clear that there is a golfers biomechanical design that defines the parameters of the structural concerns, and there are zones of employment for those structural concerns, there are dynamic condition concerns that tell us what techniques work better for each golfer, and there are functional condition concerns that show of the golfers functional limitations.

EA Tischler

May 2, 2014 at 12:02 am

Josh, let me make one more comment. The approach that Mike and I use are not new, we have been using them for over 20 years. We found them independent of eachother, did cross referencing, worked with doctors, kinesiologist, biomechanists, etc that have helped confirm much of our findings. Their is a group out of Japan finding many of the same patterns within their biomechanical approach as well. There are a variety of researchers out there confirming our findings with their own independent research. And ultimately that is what it takes for people to truly believe. For over 20 years I have been coaching the values and applications of vertical ground force. Only in the last year has there been outside independent research confirming how it works. Dr David Wright is doing great research now and has outside groups gathering independent data to test what he has already confirmed in his research about the relationship between upper arm to lower arm length relationships, core area activation and downswing slotting zones. And it all confirms what Mike and I found a couple decades ago independent of each other. By the way there are other tests the cross reference the basic tests listed in the article. The ones in the article are simply the easiest ones to demonstrate. What have both stress tests and measurement tests.

Jared L.

Apr 22, 2014 at 11:45 pm

Hey I just checked some video of my swing for a couple months back.. and I did the numbers that you said and my back swing is “If the wingspan is shorter than the height, the lead arm will align below the shoulder line at the top of the backswing in what is commonly called a flat backswing”

and my downswing is shoulder plane.. now quick question.. it sounds to me that those two together would be a fade swing right? going from flat backswing then bringing the shoulders down and to the inside? I ask cause it feels more of a natural swing to fade the ball for me (lefty) than a draw. thanks! great read!

Philip

Apr 22, 2014 at 11:06 pm

I am so waiting for the next article.

This year (finishing my 3rd month) I decided to rebuild my swing myself using a virtual simulator facility (lots of snow and ice) instead of lessons because I wanted to understand why I should do things instead of repeating exercises, but even more importantly make sure what I was doing worked for my swing (which I called a bio-mechanical swing by chance). This week I finally accepted that my backswing and downswing were different and that I have my best effortless swing when I do not try to make my backswing match my downswing.

My downswing is a torso plane swing and I noticed that if I try to have an one-plane backswing I had to loop it and place my club head above and beyond the ball. Not too consistent so I decided to just combine the two and widen my stance a bit which opened up my ability to pivot on my spine properly instead of swaying (I always fought a reverse C with longer clubs). I can now transfer my weight to my front foot with faster club head acceleration.

My measurements

* slightly (2″ with shoes on) longer arm span than height, which is normal for my family

* arm – both measure the same

Thanks for the article – perfect timing for me.

Philip

Apr 25, 2014 at 12:15 am

Follow-up

Picked up GOLF Magazine after reviewing the article. Fills in the last pieces to me understanding my swing perfectly, as well as help me understand some issues I had from lessons to eliminate my slice and lack of club head speed when I hit a ball versus my practice swing.

As a bonus, it helped me finally grasp the missing part of my setup requiring me to hold the club head above the ball. I got into the top of my backswing (using the article) and tried to move closer to the ground – figured that whatever I could move will likely be the proper adjustment – which was me sticking my butt out. I thought I was properly bending at the waist before, but I guess I was just slouching and dropping my arms.

I have gone full circle with my swing – it is now fully determined by locking my setup, loading my backswing around my spine, and firing through to my target line. My journey to playing golf instead of hitting a ball can finally begin.

Thanks again, this information has been so invaluable.

Jared

Apr 22, 2014 at 10:16 pm

Great article. My wing span is two and a half inches shorter than my height, but my forearm is one and a half inch longer than my upper arm. This sounds like it could make for a very odd looking flatter backswing with a more vertical downswing. Would you please be able to name a similar tour player I can use as a reference. Thank you for the great article.

Phil C.

Apr 22, 2014 at 6:44 pm

Good article Michael, you are very clear at explaining the concept of biomechanics and how it would dictate a swing plane. Its funny the timing of this article because I had just changed my swing to groove more to the one-plane swing concept, and with the recent improvement of 12 strokes on my best score I am a newly enthused endorser of all things one-plane.

So when I randomly came across a Mike Adams article while searching for Big Break hotties during lunch time, I spit and scoffed when i read his idea of “blowing the one plane swing theory out the dirt”. [http://mikeadamsgolf.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Cover_Swing_Tracking1.pdf] However, despite my logical and first hand belief that a single plane can deliver more consistent hits, i’m a open to learning more if it makes fundamental sense from a physics point.

The major point is the biomechanics are dictating where the swing plane sits in relation to torso and shoulders. But won’t a change in address hip angles and distance to the ball also adjust these angles in relation to the golfers body? One point in my switch to becoming more “one-plane” was more bend at the hip and wider stance. In each of your former examples if the golfer made the same adjustments they could all have low swing planes like Kuch.

What’s the benefit? If someone like Kucher comes into your class, will you ever come across a moment where you’ll instruct the student, “Hey, I think you should swing more like Senden.” A big forward moment for me was when I realized I no longer needed to “lift” my arms away from my body. The reduction in this up/down movement increased my ball striking consistency greatly; yet in your article you document that Kaymer had the exact opposite experience. Can you explain why? Because honestly it could appear just to be a case of a player returning to a swing he/she grew up with. Your point of biomechanics being the engine for improvement could be debated effectively by stating that he was just returning to his previously grooved and successful swing. Had Kaymer learned a single plane (or any other method for that matter) swing as a youth his coaching direction could be vastly different.

I’d love to hear some thoughts. Just purchased Jim Hardy’s book “Plane Truth” so i can reference if needed.

Michael Wheeler

Apr 22, 2014 at 9:15 pm

Thanks for the response. Simple answer is that if your forearm is 2 inches longer than your upper body why would try to force your plane lower to where that matches someone whose forearm is naturally shorter. When your forearm is longer than the upper arm it will set the club higher and further from the body than someone whose forearm is shorter.

Senden’s swing is different than Kuchar because Senden’s biomechanics are much different than Kuch. They both swing the way they do and are successful because it matches their biomechanics. All of the Tour players have been tested by Mike Adams and EA Tischler during the research for the certification. Martin Kaymer struggled in the lower plane because it did not match his biomechanics as his forearm is much longer than his upper arm.

Jim Hardy is an excellent teacher and is not wrong in his theory of one planers, but for golfers that have wingspans that are 4″ or more longer than their height they may react better to a lateral swing as we call it versus a rotary swing. How the arm sits at the top is dependent on that wingspan versus height number. Each of those tour players do what they do because it’s comfortable and natural to their biomechanics. There are other factors that have to be taken into account that are too many to name (rotation of the forearm for example) that would influence the swing as well. This is where going to an instructor, especially a BioSwing Dynamics certified instructor would benefit anyone.

The entire certification helps us screen the golfer to give us a blueprint of how they should swing. It helps us find a swing that matches the individual and makes it more natural to them, which a response I get most of the time from my students since learning more about BioSwing Dynamics from Mike and EA, amongst many other certified instructors like Ted Sheftic.

nick hanson

Apr 22, 2014 at 4:41 pm

Great article Michael. E.A.’s been my teacher for the last 12 years and I can say with authority that he is the expert on these theories. It’s very cool to finally see it in print at a major publication.

Thanks for the wonderful article.

Nick Hanson

Nick Randall

Apr 22, 2014 at 4:27 pm

Hi Michael, congratulations on a really well written article. I really like the premise and it seems like a nice and tidy formula, I am going to start collecting some data from the students at our golf academy and the Queensland state training squad – will be interesting to see if the numbers match up to the theory for us too.

I was under the impression that the biggest factor involved in downswing plane is your backswing plane, not necessarily your forearm to upper arm ratio. For instance if you take it back steep then it has to come down shallow and vice versa. Would it be possible to get your thoughts on that theory please?

ps. Do you know where we can access the original piece of research?

thanks

Nick

Michael Wheeler

Apr 22, 2014 at 9:00 pm

Nick, the original research is from the BioSwing Dynamics Certification, which belongs to Mike Adams and EA Tischler. However, your comment that if they swing back shallow then down steep and vice versa is not always true. The forearm length vs upper arm length is an absolute for downswing plane and not backswing plane. Backswing plane is checked by another test, but also takes into account other factor such as body size and width. There are 9 swing tracks… The golfer can come back on the hip plane (shaft plane) and then down on either the hip, torso, or shoulder plane; they could come back on the torso plane and then down on either the hip, torso, or shoulder plane; finally they could come back on the shoulder plane and then down on either the hip, torso or shoulder plane. If they come back high then come down low (shoulder backswing to torso downswing as an example) this would be considered a slot swing. If they go the other direction, low to high (hip plane backswing and shoulder plane downswing for example) that would be called a reverse slot swing. As you can see there is a lot more that a certified BioSwing Dynamics Instructor could use to fit the swing to the golfer, but these are a good base of information to see if you are working on the right things.

Hope that answers some questions…